The Improbable Voyage of the Capricornio

It was in mid winter

2004 when my friend and then workmate Germán invited me to sail

to the Comau fjord aboard his yacht Capricornio. You will understand that

at first I was a bit reluctant to go, considering that the summer before,

on the boat's and the Captain's first trip in the complicate waters of

Chiloé, more than one thing went wrong, with no electricity of any

sort on board, no radio contact, no lights, no bilge pump, the boat taking

on water like mad, the hand pump breaking down, the mast almost going overboard

when the forestay broke, and a few dozen other interesting happenings of

the kind that add spice to the seaman's life.. But then, errhm, I

thought that these nice fellows would not survive another trip without

my valuable help, and said yes!

It was in mid winter

2004 when my friend and then workmate Germán invited me to sail

to the Comau fjord aboard his yacht Capricornio. You will understand that

at first I was a bit reluctant to go, considering that the summer before,

on the boat's and the Captain's first trip in the complicate waters of

Chiloé, more than one thing went wrong, with no electricity of any

sort on board, no radio contact, no lights, no bilge pump, the boat taking

on water like mad, the hand pump breaking down, the mast almost going overboard

when the forestay broke, and a few dozen other interesting happenings of

the kind that add spice to the seaman's life.. But then, errhm, I

thought that these nice fellows would not survive another trip without

my valuable help, and said yes!

Before starting the trip, Germán sent me a big box with the

Capricornio's whole electronic outfit: VHF radio, autopilot, depht finder, etc.

It was all out of order, and my assignment was to fix it all before we

began the trip. Germán had sent the bad generator for professional

repair, so at least we would have assured electricity. I fixed all the

stuff as best I could. When something is brutally corroded by thirty years

at sea, there's only so much one can do!

The Capricornio was built mostly by Germán's father, starting

in the early seventies, and construction took many years. Germán

basically grew up on it, knows it inside and out, and recently bought it

to keep it in the family. Poor Capricornio had spent several years getting

less maintenance than necessary, which explains all the trouble on the

first trip.

I arrived by plane in Puerto Montt, where the Capricornio was waiting,

the evening before we would set sail. Germán and Michael, the third

in the group, would arrive the next morning, and it was my duty to "take

possession" of the yacht, check that all was right in it, and go buy the

groceries in the early morning, so we could weigh anchor as soon as the

two arrived.

The flight was interesting, because the weather was very foul. The Boeing

bounced around, I knocked my head on the side despite the safety belt,

and the landing was with nearly zero visibility in a true Puerto Monttian

rain. This city is famous for it, and a slogan says Puerto Montt, where

the rain turns into song. Walking ten steps from the airport hall to

the bus was enough to get me soaked. Once downtown, I took a taxi to the

marina, and when I arrived there, it was already pitch black night, but

it had miraculously stopped raining! I introduced myself to the marina's

administrator, who assured me that it had rained in this way, almost nonstop,

for the last three months. When I explained that I wanted to board the

sloop Capricornio, he looked funnily and said: "I presume you mean the

Submarine

Capricornio?"

Well, it wasn't that bad after all! It was still afloat, even if just

a little. The bilge pump had failed again, and knowing that the owner was

coming, the marina people had left it that way so we could fix it ourselves.

So the guy brought me to the boat, said good night, and left. And there

I was, inside a perfectly dark, perfectly unknown boat, hunting for a

light switch and finding none. Knowing that there were enough flashlights

on board, I didn't bring my own, and now I regretted that. After much tapping,

bumping my head into unidentified obstacles of all sorts, I finally found

a switch, but nothing happened when I flipped it. I kept feeling for something,

anything,

that would be so kind and give me a few photons, but first managed to get

my feet and shoes soaked, because there was water rising above the floor.

Then I found something that felt like a box of matches. Great! But they

didn't light - they were totally soaked in the extreme humidity! The search

continued, and the next promising object that turned up was a flashlight

- but without batteries.

Opening

my path into the bow cabin, I found another flashlight. It was heavy, which

meant that this one actually had batteries. Marvelous! But it didn't

work either... So, the problem could be the batteries, the bulb, or a contact.

I crawled back, found the other flashlight again, put the batteries of

the second one into the first, and Eureka, I had light!!!

Opening

my path into the bow cabin, I found another flashlight. It was heavy, which

meant that this one actually had batteries. Marvelous! But it didn't

work either... So, the problem could be the batteries, the bulb, or a contact.

I crawled back, found the other flashlight again, put the batteries of

the second one into the first, and Eureka, I had light!!!

Armed with a weak but functional flashlight, I found an electrical panel,

with all main switches in OFF position. I switched them all on. Still no

cabin lights. Then I found a panel voltmeter, showing accurately zero Volts.

Either the batteries were flat, or there was a main switch somewhere.

Only after taking off the engine compartment covers and following the wires, did

I find this switch, conveniently hidden in a place nobody would ever find

it, if he hadn't the good idea to check the cable runs! I threw that big

switch, and Eureka squared, now I did have functional cabin lights!

The next thing was lifting some floor boards, and diving for the bilge pump.

After getting as wet as one possibly can, in the icy and dirty bilge soup,

I found it and brought it up. Fortunately the problem was minor: The pump

had eaten little fibers from a frayed line, and these had jammed it. I

cleaned it, reinstalled it, combed the bilge for debris, found the rotten line

and fished it out, and then the pump started working and pumped the bilge

empty. The Submarine Capricornio majestically rose out of the water and

became a real yacht!

My first duty done, I went to sleep. Fortunately my sleeping bag was dry,

but the mattress below was not. Actually, nothing that had been in the

boat was dry, an effect of the continuous rain and the water in the bilge,

which kept the relative humidity as close to 100% as it can get! It rained

most of the night, but in my goose down sleeping bag I was warm and comfortable.

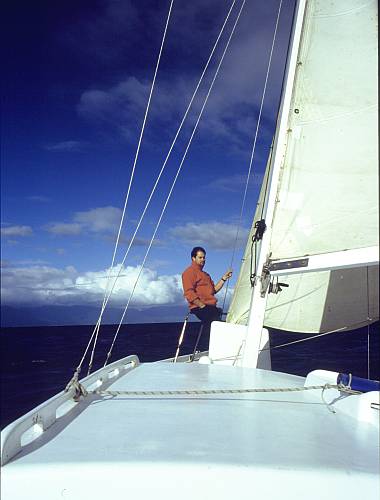

It's

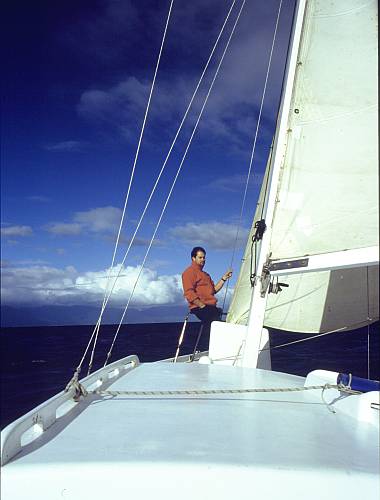

time for an introduction: This is the much bespoken Germán. From

now on we will respectfully call him "the Capt'n". Here he is showing his

impressive ability to give orders. The other main actor of this story,

Michael, will be often referred to as "The Intrepid Boatswain". You will

soon see why, so don't ask.

It's

time for an introduction: This is the much bespoken Germán. From

now on we will respectfully call him "the Capt'n". Here he is showing his

impressive ability to give orders. The other main actor of this story,

Michael, will be often referred to as "The Intrepid Boatswain". You will

soon see why, so don't ask.

Actually, we met at the supermarket, where I was still choosing food

when the two arrived downtown. That was great, because there was no way

I could have carried two big carts worth of stuff to the marina! Even

for three, it was a lot of work. You may know that I'm not the kind of

guy who likes eating noodles and rice day in, day out, so I planned a better

diet, with lots of vegetables, good cheese, fruit, several different sorts

of bread, all kinds of stuff to put on it, fine herbs, good olive oil,

an assortment of fine wines, and a long etc. When the two guys came, they

mostly agreed with my purchases, but added about three quarters of a cow,

cut into convenient chunks. I'm not much of a meat-eater, but these two

sure are!

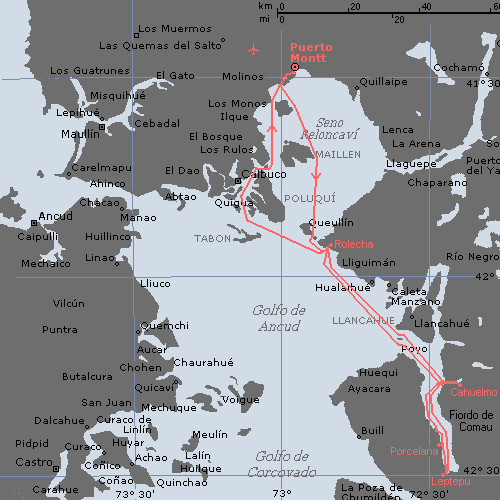

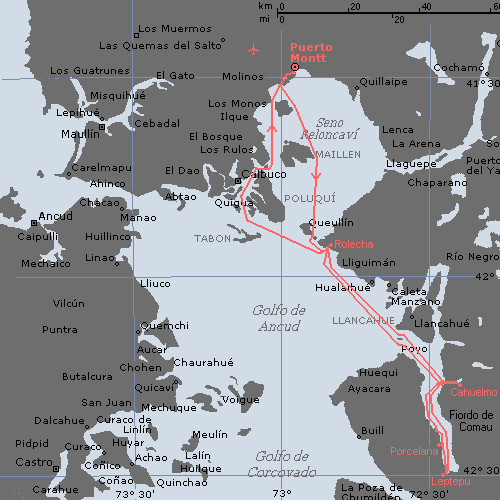

We threw all the

purchases into the sloop, set sail and sailed out on the Tenglo channel,

then straight south across the Reloncaví bay. This map, artfully

drafted by fellow sailor Alfonso Gonzales for this story, shows the area and

a rough sketch of our trip. Basically, we went south to the Comau fjord,

and then along all its length, visiting the beautiful places along it, and

taking refuge in sheltered bays during the nights.

We threw all the

purchases into the sloop, set sail and sailed out on the Tenglo channel,

then straight south across the Reloncaví bay. This map, artfully

drafted by fellow sailor Alfonso Gonzales for this story, shows the area and

a rough sketch of our trip. Basically, we went south to the Comau fjord,

and then along all its length, visiting the beautiful places along it, and

taking refuge in sheltered bays during the nights.

If you are somewhere in this large round world and you have no idea where to

find this on your world map, look for Chile first (that's in South America,

just in case :-), then look where the country starts dissolving into water

roughly at 42 degrees southern latitude. That's the place.

It had stopped

raining, the sun had come through, the wind was perfect, and we enjoyed

it. Most of the time I would sit at the helm. The Capt'n loves to hang

out at the bow, so that's what he did most of the time. Michael, instead,

is the kind of guy who can't stay put for more than five minutes. He was

milling around, stowing away our supplies, cleaning up, cooking, fixing

things, reading the map, navigating, and so on. Sometimes I tried

to switch places with him - but I didn't last! I have an easily upset stomach,

and when the vessel rolls and pitches like it loves to do when the wind comes

from near the stern, like here, I must stay on deck and look at the horizon,

or I would soon feed the fish. And so, if I have to stay on deck anyway,

I might as well hold the helm...

It had stopped

raining, the sun had come through, the wind was perfect, and we enjoyed

it. Most of the time I would sit at the helm. The Capt'n loves to hang

out at the bow, so that's what he did most of the time. Michael, instead,

is the kind of guy who can't stay put for more than five minutes. He was

milling around, stowing away our supplies, cleaning up, cooking, fixing

things, reading the map, navigating, and so on. Sometimes I tried

to switch places with him - but I didn't last! I have an easily upset stomach,

and when the vessel rolls and pitches like it loves to do when the wind comes

from near the stern, like here, I must stay on deck and look at the horizon,

or I would soon feed the fish. And so, if I have to stay on deck anyway,

I might as well hold the helm...

I was a bit worried about the batteries. When we weighed anchor, they

were at only 11.5 Volt, which means they were deeply discharged. The Capricornio

has a solar panel, but in the very bad weather all the previous months

the panel had been pretty useless. Now it was generating a little, but

not nearly enough. Remember this was in winter, days were short, nights

very long. So I suggested to run the engine despite the good wind, just

to charge the batteries. So we did. But an hour later I was shocked to

see that the batteries, far from charging, had dropped to 11.2 Volt! Once

again the engine compartment covers came off, and I crawled in, armed with my

multimeter. The Capt'n throttled up until almost bursting the old engine,

to no avail: The freshly and "professionally" repaired generator was as

dead as an old doornail!

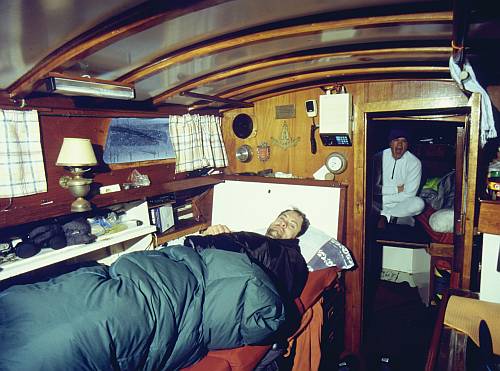

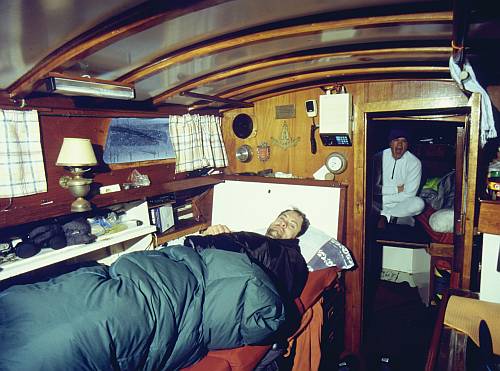

We sailed all

the way to Rolecha, a small village along a bay that offers good anchoring

ground and some protection. Soon the evening came, and on this photo you

can see how our first idyllic night on the Capricornio went: Working with

battery-powered headlamps to conserve the little remaining charge on the

main batteries, the whole crew is at work. The Boatswain was happily filing

away at a fitting he needed to complete an ultra-effective pump setup.

After the last trip, where he got duly fed up with hauling buckets, he

now wanted several pumps in good working order. The Capt'n is assisting

that noble effort, while I'm entirely devoted to the generator.

We sailed all

the way to Rolecha, a small village along a bay that offers good anchoring

ground and some protection. Soon the evening came, and on this photo you

can see how our first idyllic night on the Capricornio went: Working with

battery-powered headlamps to conserve the little remaining charge on the

main batteries, the whole crew is at work. The Boatswain was happily filing

away at a fitting he needed to complete an ultra-effective pump setup.

After the last trip, where he got duly fed up with hauling buckets, he

now wanted several pumps in good working order. The Capt'n is assisting

that noble effort, while I'm entirely devoted to the generator.

This generator isn't a simple thing: It was born in the glorious times

when alternators were inexistent, and when manufacturers had noticed that

an engine needs a generator only while it's running, and a starter only

while it is not yet running, and that it would thus be a brilliant

money-saving idea to combine both functions in a single machine! This contraption

is called a dynastarter, and is basically a four-pole compound motor

designed as a compromise, that does rather mediocre duty as a starter,

and then delivers equally mediocre performance as a dynamo.

This guy was working well as a starter, but not at all as dynamo. A

thorough inspection brought up no immediately obvious problems. The resistances

all seemed normal, the brushes were not marvelous but OK. Then I had a

bright idea. Yes, I do have them from time to time, so don't laugh. I removed

the rotor from the machine, dug out my little pocket compass, which fits

inside the stator, and used it to measure the remnant magnetic field, noting

down which poles were north and which were south. Then, using a battery

taken from a flashlight, I applied some current to the series field winding.

As expected, the magnetic field intensified. Then I applied the battery

to the shunt field winding. Flop! The compass needle turned all the way

around! The north poles had become south poles! Bingo! The idiot who "professionally"

repaired this dynastarter had connected the shunt field backward! So this

machine would have needed to work in one rotation sense as a starter, and

in the opposite sense as a generator... Not very clever indeed! :-)

I had brought a 12 Volt soldering iron aboard, but it was a small one,

for electronic purposes. I could not unsolder and resolder the field connections

with it. So I cut some wires, spliced them as best I could to reverse the

shunt field, and then the Capt'n reinstalled his dynastarter, with open

cover and dangling wires.

When we started

the engine, the generator came to life, and delivered a huge current, much

larger than it should... Obviously the regulator, one of those old-style

electromechanical things, wasn't working very well. It did regulate, in

some way, but at a much too high level. So we regulated the generator output

via the engine throttle... We left the engine running for a good while,

watching with big smiles how the battery voltage climbed, and soon came

into the green range. This pretty much saved the trip! Actually the Capricornio

can sail without electricity, as it did in summer, but in winter that's

even more uncomfortable. Oil lamps of Aladdin's tradition give only so

much light, and don't power a VHF radio very well...

When we started

the engine, the generator came to life, and delivered a huge current, much

larger than it should... Obviously the regulator, one of those old-style

electromechanical things, wasn't working very well. It did regulate, in

some way, but at a much too high level. So we regulated the generator output

via the engine throttle... We left the engine running for a good while,

watching with big smiles how the battery voltage climbed, and soon came

into the green range. This pretty much saved the trip! Actually the Capricornio

can sail without electricity, as it did in summer, but in winter that's

even more uncomfortable. Oil lamps of Aladdin's tradition give only so

much light, and don't power a VHF radio very well...

The engine is an ages-old Volvo Penta two cylinder diesel. It delivers

impressive 15 HP, which isn't very much for a 9-meter sloop that weighs

four tons. But at least it was running very well, so well that we came

to call it the only reliable component of the Capricornio! Its trademark

propp-propp-propp

sound

instilled an enormous confidence!

This engine has an interesting history: It spent some time on the sea

floor, after its first vessel sank in a storm. It was rescued, repaired,

and installed in the then new Capricornio. Here it ran for many years,

then spent some years sleeping, then it was overhauled and on this trip

it worked like new. And a great feature is that it can be started with

a crank, if necessary! But that requires a guy with real muscles! Many

people can't even start to move it!

If you are surprised by the odd air filters, don't be: They were borrowed

from two Citroën 2CV! The Capt'n is crazy for those equally historic

cars...

The array of pipes and things in the foreground and left is mostly Michael's

work. The brass device is a Jabsco high flow pump, driven by the engine,

which can keep the boat afloat even with quite large holes in the hull

- as long as the engine works. The black device is a hand-driven pump.

It was intensively used on the last trip, until its handle broke from fatigue,

and the intrepid boatswain had to go ashore, fell a small tree, and use

it to make a new handle, which sticks out proudly here. The stuff behind

the manual pump is a system of valves that allows priming the Jabsco pump

with bilge water brought up by the manual pump, while avoiding any water

entry through the outlet pipe. Believe it or not, it all worked fine, and

gave us more hopes of staying afloat until the end of the trip!

After spending

most of the night working, morning caught us much too early. But it was

a beautiful, sunny morning, with completely cloudless sky. Don't forget

that this was in mid winter, in a zone where it rains so much that people

have to turn the rain into song! So we set sail and aimed south, towards

the Comau fjord.

After spending

most of the night working, morning caught us much too early. But it was

a beautiful, sunny morning, with completely cloudless sky. Don't forget

that this was in mid winter, in a zone where it rains so much that people

have to turn the rain into song! So we set sail and aimed south, towards

the Comau fjord.

You can see here that the Capt'n's bunk is also the dinner table. It

only has to be installed a bit higher. Oh yes, and the dinner table is

also the navigation table. Often these two uses conflict. In contrast,

the Capt'n's sleeping doesn't conflict with either dinner or navigation:

If the table is needed, the Capt'n is simply thrown out of his bunk!

Oh, I almost forgot: The Capt'n's bunk, the dinner table, and the navigation

table are also the workshop bench. Did I talk about conflicts? Well, this

is how things go in a small yacht! The bow cabin, where Michael and

I slept, is also the sail stowage room, holds the freshwater tanks, some

life vests, and much of the food supply. The kitchen sink doubles as bathroom

sink. It's the only place where you can draw freshwater. And now, please

don't ask me whether the bottled drinking water supply and the loo share

the same location. I won't answer that question!

Our sailing that

day didn't last very long. In near gale wind, the jib went overboard

when the rotten halyard decided to give way. The Capt'n had thoughtfully

installed a backup halyard, so we fished the sail out of the water and hauled

it up again. But after a while, the sail again went overboard, this time

because the top block failed! Now there wasn't much to do, we could no

longer use the jib. Climbing the mast while the sloop rolls is not a very

good idea. And without a jib, only under main sail, this boat does

not behave very well. So we took the main sail down too, and continued

the day's trip under engine power.

Our sailing that

day didn't last very long. In near gale wind, the jib went overboard

when the rotten halyard decided to give way. The Capt'n had thoughtfully

installed a backup halyard, so we fished the sail out of the water and hauled

it up again. But after a while, the sail again went overboard, this time

because the top block failed! Now there wasn't much to do, we could no

longer use the jib. Climbing the mast while the sloop rolls is not a very

good idea. And without a jib, only under main sail, this boat does

not behave very well. So we took the main sail down too, and continued

the day's trip under engine power.

The Volvo Penta in the Capricornio is intended only as an auxiliary engine,

not as the main source of propulsion. The sloop is slow under sail, and

it is very slow when using just the engine! Every little fishing

boat seemed to go three times as fast as we did, and that's not an exaggeration

considering that we were doing just over four knots of speed! Even so,

Michael calculated that we would reach our destination for the day, the

narrow fjord of Cahuelmó, just before darkness. So we were in good

mood, relaxed, cooked a meal, fixed things, and above all, enjoyed the

landscape.

Southern Chile is one of the very few places in the world where you

can sail in a maze of channels, protected bays and more open waters, around

thousands of little and larger islands, most of them uninhabited and never

damaged by humans, always within sight of snowcapped mountains. The snow

in some places reaches right to the sea, and wherever there are no people,

the forest reaches the sea. There are few beaches; at most places the shores

are rocky and very steep. It's common to sail within an easy stone throw

of the shore, while the water is so deep that the depth finder is out of range!

The Capt'n was

enjoying the view. The Capricornio had spent almost all of its previous

years in Antofagasta, a desert port, where the coast is invariably dry

and sterile. Traveling along dense jungle on his yacht was a welcome change.

The Capt'n was

enjoying the view. The Capricornio had spent almost all of its previous

years in Antofagasta, a desert port, where the coast is invariably dry

and sterile. Traveling along dense jungle on his yacht was a welcome change.

If my memory is right then the island on the right is Liliguapi, and

that on the left is Llancahué. We are on the Comau channel, going

to the Comau fjord in the background. The mountains straight ahead, all

the way to the coast, are part of the Pumalín park, a private nature

preservation area larger than many national parks, which has generated

much controversy because it is owned by a foreigner and extends all the

way from the sea to Chile's border with Argentina. Across the border, his

wife holds similar extensions of land. Even so, at the time of writing

this, 2005, it seems that most of the problems have been worked out, and

Pumalín appears on recent Chilean maps with the same status as a

national park.

If you ask me, my opinion is pragmatic: Any initiative to preserve

nature, in an area as beautiful, fragile and special as this, is most welcome,

no matter whether it's the government or a private person who does it,

and no matter whether the initiative comes from a Chilean or anyone else.

The alternative to preservation is typically a sparse settlement, clear-cutting

the forest, followed by dramatic soil degradation caused by erosion from

the wind and the very heavy rain. The waterways get choked by runoff, and

the area turns into a steppe with very little vegetation. Such damage has

been done to large areas of Chile, including some just 200km south from

here. Comparing the view of such a degraded place (see an example),

to a pristine one like our Capt'n is admiring here, brings dramatic clarity

to the need for preservation.

The Capt'n is

taking a turn at the helm. We still couldn't use the autopilot, because

the sloop's deck had been fiberglassed recently, and in

the process the connector for the autopilot had been removed! With so many

more important things to repair, we had not yet found the time to reinstall

it.

The Capt'n is

taking a turn at the helm. We still couldn't use the autopilot, because

the sloop's deck had been fiberglassed recently, and in

the process the connector for the autopilot had been removed! With so many

more important things to repair, we had not yet found the time to reinstall

it.

Most of the time I was at the helm, simply because that way I didn't

get seasick so easily. But when the water was very smooth, like this evening

approaching Cahuelmó, I could actually go below deck and fix things,

cook, clean my photo gear which always got salt water on it and didn't

like that treatment, and then use it to make some nice photos.

I hope some day scanners and computer screens will reach the quality

level required to reproduce the starkly beautiful look of images like this,

when projected from a slide, through a good lens, onto a large screen...

Until then, you will have to bear with these computer images in lousy resolution

and even more lousy contrast range, or come to Chile and attend one of

my slide shows!

Do you see the fishing rod? Well, Michael somehow had the crazy idea

that the sea would be full of fish, and that these fish would like to

bite his hook. But southern Chilean fish are clever, and when a shiny thing

hangs from a moving vessel, they know better than to bite it! We trailed

the fishing hook during our entire trip, and caught absolutely nothing!

The thing was a sea anchor, to keep us from overspeeding...

Michael tried every hook he had, with artificial lures of different sorts,

with baits consisting of kitchen residues, fresh shellfish gathered at

the anchorages, and a lot more things. Unfortunately we couldn't eat the

shellfish ourselves, because there was an infestation of Red Tide, which

accumulates in shellfish, does not harm them, but is so toxic to humans

that a single infected shellfish can kill the person who eats it! So we

kept trying them as bait. Only later did we realize that our Intrepid Boatswain

missed the most important of experiments: He should have taken a waterproof

pen and written a little sign: Dear Mister Fish, please bite on this

nice thing. You will be hooked, I promise! Yours truly, Michael.

Maybe

that would have worked better!

Having no fish to cook, that evening we dined on my special issue Greek

Salad, with gherkins, tomatoes, olives, goat cheese, extra virgin olive

oil, oregano, and some secret ingredients which I won't divulge here. The

glasses were filled with a nice red wine. It was accompanied by one beef

steak for me, three for the Intrepid Boatswain, and eight for the Capt'n.

After all, he deserved them because he had actually worked this day, taking

a turn at the helm for all of fifteen minutes!

We anchored

as far inside in the Cahuelmó fjord as we could get. The bay continues

to the left from here, but with shallow waters that at the lowest tide

are too shallow for the Capricornio.

We anchored

as far inside in the Cahuelmó fjord as we could get. The bay continues

to the left from here, but with shallow waters that at the lowest tide

are too shallow for the Capricornio.

Anchoring in these waters is not as easy as throwing the anchor and

relying on it! The sea floor goes down at an angle steeper than 45

degrees, just like the mountains go up! So the anchor will slide down,

pull the us away from shore, until it hangs free from its chain and the

boat drifts off! Instead, the anchoring process here

consists of getting close to shore, setting out the dinghy, letting the

Intrepid Boatswain climb the shore, and tie a line to a sturdy tree or a

rock. Then the boat is moved until the depth finder reads a convenient depth,

maybe 15 meters. Only that often it doesn't read anything, because

the bottom is so steep that it doesn't get any reflections! Then,

an old fashioned piece of rope with a weight at the end and marks along

its length has to be used

to sound the depth. When deciding which depth is good, one has to keep

in mind the tides, because they are pretty extreme here, sometimes reaching

up to eight meters! Anyway, at the proper location the line is made fast to

the stern, and the bow anchor is lowered. The anchor slides down and pulls

the chain and rope tight, while the boat ends up in a fixed position,

looking straight away from shore, ready to sprint if anything requires

this action!

I shot this photo in the early morning - our third day at sea, and the

second completely cloudless one, in mid winter in one of the rainiest places

in the world!

When I returned

from my early morning photo trip, the rest of the crew was just thinking

about the remote possibility of trying to wake up. Look closely at the

face of the Intrepid Boatswain in the background, and you will get the picture!

When I returned

from my early morning photo trip, the rest of the crew was just thinking

about the remote possibility of trying to wake up. Look closely at the

face of the Intrepid Boatswain in the background, and you will get the picture!

It always took quite a bit of self-control to get up. During the day,

the temperature was one or two degrees above freezing, but in nighttime,

it was well below. Whenever we had the engine running, and up to two hours

after, we had some heating from it, but in the early morning it was definitely

cold. Getting out of the nice warm sleeping bags, into the cruel, solid-frozen

world, was never easy!

It's interesting to note how we internalized the low temperature. The

second evening, while I was clearing up the mess in the galley/washing room/Capt'n's

cabin/navigation room/workshop/radio room, I kept tripping over the half

cow (one quarter of the original three quarters had already been consumed).

So I handed the parcels of meat to the Capt'n, who was standing on deck

staring into the sky (he says that's his duty too, as it is necessary for

forecasting the weather). I said: "Put this in the freezer, please", and

he placed it on deck, in a spot protected from spray, without even thinking

twice about the freezer thing! It was too plain obvious that the entire

deck could be used as a big freezer!

But they finally did get up, and there was work to do, specially for

The Intrepid Boatswain!

The only way

to fix the problem with the jib was climbing the mast and installing

a new top block. That's definitely not a task for the faint of heart,

and a certain degree of bodily fitness isn't unwelcome either. The day

and location was perfect for it, with absolutely still water, so that the

Capricornio didn't move, unless we did.

The only way

to fix the problem with the jib was climbing the mast and installing

a new top block. That's definitely not a task for the faint of heart,

and a certain degree of bodily fitness isn't unwelcome either. The day

and location was perfect for it, with absolutely still water, so that the

Capricornio didn't move, unless we did.

Michael improvised a climbing harness, which was tied to the main sail halyard.

Then he climbed up, with us other two helping

at the sail winch. In some countries they make contests of "climbing the

greased pole". Well, this pole wasn't greased, but it was rather slippery

anyway, thanks to many layers of oil paint on the Oregon Spruce. With some

help from the halyard, he was up at the mast top in a matter of a minute.

There he secured his harness to an additional hook, and freed up his hands

to work.

So, now at least you know why we call our Boatswain "intrepid"!

The installation of the new block and halyard went quickly. But he also

took time to check the VHF antenna connection. This antenna, despite being

mounted at the mast top a good 13 meters above sea level, was providing

very poor performance. Michael isn't a radio man - that job is mine - but

it was obvious enough for him that the antenna needed service, as it was

heavily corroded. But we had no means on board to try that, and since the

antenna still worked well enough to have radio contact with passing vessels

and coastal stations within sight, he left it at that.

When Michael

was ready with the hard work, he devoted some time to tourism, and asked

us to send up his camera. We had an auxiliary line in place to move up

and down all the tools and materials he needed to fix the sail problem,

and so his entire camera bag went up the mast. Thanks to this, now you

know not only why we consider him intrepid, but also now you know how a

sloop looks from 13 meters up on the mast! It looks pretty small,

don't you think?

When Michael

was ready with the hard work, he devoted some time to tourism, and asked

us to send up his camera. We had an auxiliary line in place to move up

and down all the tools and materials he needed to fix the sail problem,

and so his entire camera bag went up the mast. Thanks to this, now you

know not only why we consider him intrepid, but also now you know how a

sloop looks from 13 meters up on the mast! It looks pretty small,

don't you think?

Thanks, Michael, for this photo!

Actually, before climbing the mast of such a boat it's a good idea

to do the math. It's easy: The sloop has a known weight at a known depth

under its center of gravity, defined mostly by the lead weight carried

in the keel. It's about 1400kg, 1.4m under water. A typical Intrepid Boatswain

will weigh about 75kg and his center of gravity will be about 12m

above the waterline. That works out well enough. But if we also sent up

the belly-fitted Capt'n to help Michael, and specially if that is done

after the Capt'n has eaten eight beef steaks, the poor Capricornio would

feel very inclined to take serious measures against such abuse, and would

dunk both of them into the chilly water through its inclination! :-)

This was the

culprit for Michael's skyward trip. It looks like the plastic wheel became

brittle, probably due to UV exposure, and broke, which made the halyard squeeze

itself into the little room between the broken wheel and the sides, thus

bursting the riveted axle and coming down.

This was the

culprit for Michael's skyward trip. It looks like the plastic wheel became

brittle, probably due to UV exposure, and broke, which made the halyard squeeze

itself into the little room between the broken wheel and the sides, thus

bursting the riveted axle and coming down.

It's always a riddle what materials to use on a sailing boat. Each

material has its own set of disadvantages. Plastic is impervious to rusting,

but degrades with sunlight. Metal is impervious to sunlight, but it rusts

- and that's true even for so-called stainless steel! The rusting is much

slower, true, but specially in the presence of abrasion, stainless steel

does corrode. And it's not as simple as saying "stainless steel", and "plastic"!

There are countless variations of each, each with its own strengths and

problems.

Now, if abrasion is a problem, bronze can be quite good. But don't take

the much more common brass for bronze! Many people think they are the same

stuff, only because their colors are quite similar. And of course, don't

put two different metals in electric contact with each other. If you do,

the metal that's higher on the electrochemical scale will be just fine,

and totally eat up the other one! That process works surprisingly fast

when there is salt water around. In this regard, plastic shines. But when

the sun shines, plastic stops to shine... specially when it is white and

even worse when it is transparent.

All the above is just to convince you that our dear, infallible Capt'n,

deserves to be excused for having installed the wrong kind of block atop

his mast!

For the rest of

the day, we went to the thermal baths of Cahuelmó. They are located

at the end of the fjord, accessible only in a small boat during high tide.

The Capt'n told the Intrepid Boatswain to check the amount of fuel in the

dinghy's outboard engine. Michael had a look, said "more than enough",

and off we went, outfitted with towels, photo gear and a light picnic.

For the rest of

the day, we went to the thermal baths of Cahuelmó. They are located

at the end of the fjord, accessible only in a small boat during high tide.

The Capt'n told the Intrepid Boatswain to check the amount of fuel in the

dinghy's outboard engine. Michael had a look, said "more than enough",

and off we went, outfitted with towels, photo gear and a light picnic.

When we had done about half the way, suddenly the engine sputtered,

then stopped. The fuel tank was dry! Mr. Boatswain muttered something in

the line of "never thought this damn thing burns that much fuel", but that

insight didn't help now. You have permission to guess who had to row us

the rest of the trip!

Once ashore, we found this nice place, with some rustic installations,

consisting mostly of bathtubs dug in the soft rock, a simple open shelter

for rainy days, and a sign that welcomes visitors, invites them to enjoy

the place, and asks them to avoid any damage and to take any trash back

with them. This thermal bath, along with everything you can see on this

picture except the boat, is part of the Pumalín park.

This is the main

hot spring. A nice creek of boiling hot water comes out of the ground,

between ferns and other plants adapted to the higher temperature around

the hot water. Even in the water proper there is life, with algae and bacteria

adapted to the very high temperature. The water is much too hot to put

your hand in at this place! The remains of insects litter the creek. These

are simply not programmed by nature to understand that water can be unhealthily

hot, and so they sometimes get too close, or fall in. Eventually Darwin

will work his ways here, and natural selection will produce a population

of insects who know how to respect hot water. But obviously, the process

is still under way.

This is the main

hot spring. A nice creek of boiling hot water comes out of the ground,

between ferns and other plants adapted to the higher temperature around

the hot water. Even in the water proper there is life, with algae and bacteria

adapted to the very high temperature. The water is much too hot to put

your hand in at this place! The remains of insects litter the creek. These

are simply not programmed by nature to understand that water can be unhealthily

hot, and so they sometimes get too close, or fall in. Eventually Darwin

will work his ways here, and natural selection will produce a population

of insects who know how to respect hot water. But obviously, the process

is still under way.

The water runs off through channels that allow it too cool off until

it has reached a temperature that no longer burns bathers. One can build

little dams in some places, and open others, to choose how much distance

the water moves, and how much it cools, until reaching the first pools.

Our hydraulic engineer Michael, the very same guy who build the Capricornio's

pumping plumbing and left us stranded without fuel, was in his element

here, and brought the water to perfect temperature.

Ha, that's life!

Resting in the warm water, under blue sky, surrounded by some of the world's

most pristine nature, away from the haste, noise and stink of cities, nibbling

on assorted nuts and fruit!

Ha, that's life!

Resting in the warm water, under blue sky, surrounded by some of the world's

most pristine nature, away from the haste, noise and stink of cities, nibbling

on assorted nuts and fruit!

We were a little worried about the low tide starting soon. When that

happens, the currents become a bit strong for the dinghy, very specially

when the engine has no fuel left... And a while later, there is no water

left, only mud, densely populated by shellfish with sharp edges. And if

there's one thing an inflatable boat doesn't like, it's being dragged over

sharp shellfish! But the water was so relaxing that the Capt'n stretched

his tide calculations as far as he could, and we enjoyed the place royally.

This

is the view to the other side, from the thermal pool. We just had to turn

our heads to look at this. Michael is also an avid mountain climber, and

can be a bit hard to hold back. He almost ran away and up this mountain!

And to speak the truth, I was really tempted to accompany him on that noble

endeavor, if it were not for my stupid arthritic hip that has kept me mostly

away from long walks and climbs in recent years.

This

is the view to the other side, from the thermal pool. We just had to turn

our heads to look at this. Michael is also an avid mountain climber, and

can be a bit hard to hold back. He almost ran away and up this mountain!

And to speak the truth, I was really tempted to accompany him on that noble

endeavor, if it were not for my stupid arthritic hip that has kept me mostly

away from long walks and climbs in recent years.

This picture was shot through a selected Pentax 200mm f/2.8 extra low

dispersion lens, used at its optimal aperture. The original slide shows

an amount of detail so impressive that one thinks each snow crystal registered

separately on the film! Of course, the 500-pixel-wide scan cannot start

to do justice to this, so, please imagine how the slide looks! :-)

At 15

hours the sun set behind the tall mountains, and we returned to the Capricornio.

We scratched the mud in many places, had to turn around a few times, and

then the Capt'n had to help rowing to get us across the current caused

by the river which empties into this bay, or we would have drifted past

the yacht and out onto the sea.

At 15

hours the sun set behind the tall mountains, and we returned to the Capricornio.

We scratched the mud in many places, had to turn around a few times, and

then the Capt'n had to help rowing to get us across the current caused

by the river which empties into this bay, or we would have drifted past

the yacht and out onto the sea.

Night falls by about 17:30 in this time of the year, so the evenings

were long. Several times we went ashore in darkness, and at other times

we played around with the dinghy, properly refueled, shooting pictures.

This one was taken with flash lighting. The distance necessary to get the

whole sloop onto a photo was much larger than what the flash is rated to

cover, but with a shiny white yacht, that's no problem! Michael was surprised

when he first saw this photo. He thought it would turn out black, like

all those countless photos shot by silly people with little automatic cameras,

trying to use the internal flash to light a landscape many kilometers away!

Well, like many people these days, he didn't consider the abilities of

an f/1.4 lens combined with the high reflectivity of the white paint!

The next day

we left Cahuelmó and continued south along the Comau fjord, in an

incredible weather. This was the third cloudless day in a row! If

it hadn't been for the low temperature and the snow on even the smaller

mountains, it would have been hard to believe that this was mid winter!

The next day

we left Cahuelmó and continued south along the Comau fjord, in an

incredible weather. This was the third cloudless day in a row! If

it hadn't been for the low temperature and the snow on even the smaller

mountains, it would have been hard to believe that this was mid winter!

Since the hot baths of Cahuelmó had been so enjoyable, we wanted

to try more such places. Everyone in the area recommended the thermal springs

of Porcelana. But every person we asked gave us different directions! So

we took down the sails, and motored very slowly along the suspect coast,

trying to detect any clues to where it could be. Michael tried to

extract all possible clues from the maps, which listed a Porcelana river,

a Porcelana bay, a Porcelana village, a Porcelana farm, a Porcelana point,

a Porcelana salmon hatchery, all at different places, but no Porcelana

thermal baths at all!

We ended up anchoring in a little bay and going ashore in the dingy,

at a beach that looked like it had some human traffic. There was a little

trail, and after five minutes walking we reached a little ranch house.

Michael called loud, because when in this very sparsely populated area

visitors arrive unexpectedly, it's not unheard of that the houseowner reacts

in panic and uses his shotgun! But that's rare, fortunately. In such places

most all people are good, and welcome visitors.

The owner of the little ranch turned out to be a friendly man, who came

out of his house to welcome us. He lived there, in the middle of paradise,

with his wife and children, raising cattle and planting some subsistence

crops. He had built quite a nice little world, with a water turbine in

a stream that provided him electricity. He had a refrigerator, a TV, even

a marine radio that served as emergency link to the "civilized world".

When I see people living like this, I can't help the impression

that they are hugely more civilized than we city dwellers are.

The rancher told

us exactly where the thermal springs were located. But the anchorages near

that place were openly exposed to the wind and waves at that moment, and

since it was getting late and the wind kept increasing, we decided to sail

all the way to Leptepu, the last corner of the Comau fjord. There

we reached a very well protected little bay, with two large anchored buoys

floating near a shuttle ramp. This was a port built for Ro-Ro ships that

were supposed to land cars and trucks for a very short stretch of Chile's

Southern Road, but later this was found uneconomical and now this stretch

of road is skipped and the Ro-Ros bring the vehicles directly to the next

port. So we took possession of one of the buoys, and made fast to

it.

The rancher told

us exactly where the thermal springs were located. But the anchorages near

that place were openly exposed to the wind and waves at that moment, and

since it was getting late and the wind kept increasing, we decided to sail

all the way to Leptepu, the last corner of the Comau fjord. There

we reached a very well protected little bay, with two large anchored buoys

floating near a shuttle ramp. This was a port built for Ro-Ro ships that

were supposed to land cars and trucks for a very short stretch of Chile's

Southern Road, but later this was found uneconomical and now this stretch

of road is skipped and the Ro-Ros bring the vehicles directly to the next

port. So we took possession of one of the buoys, and made fast to

it.

This photo was shot with a half-second exposure time from the dinghy!

Take that! The water was so incredibly calm that I could pull off this

trick.

This was the best night of all. No fear of dragging the anchor, absolute

protection from any storm that could come up, a beautiful landscape, still

being mostly clean from bathing at Cahuelmó, and the promise of

the next warm bath in Porcelana. On top of this, the Capricornio was improving

steadily, with all the minor and major fixes we were doing. When we set

out from Puerto Montt, none of the navigation lights were working. Along

the trip I fixed wiring, fuse boxes, distribution cabling, and so on, and

at this time we had all the lights we needed. We had also finally reinstalled

the connection for the autopilot. The speed log wasn't working, but that's

a minor thing because we had a GPS receiver which could supply speed data.

The sails were all fine, the engine too, even the generator was still working,

the solar panel had gotten lots of sun. The main problems were in the radio

area: The VHF radio really didn't reach far with the corroded antenna,

and the Capt'n was missing some music! The Capricornio used to have a car

radio, but that one went away into a better life shortly before the deck

was fiberglassed, because there were leaks and one of these was just above

the radio!

The next day

we went to the Porcelana thermal baths in the dinghy. I can assure you,

this time our Intrepid Boatswain filled up the outboard engine's tank to

the brim, and then he left the fuel canister in the boat, just to be sure!

The next day

we went to the Porcelana thermal baths in the dinghy. I can assure you,

this time our Intrepid Boatswain filled up the outboard engine's tank to

the brim, and then he left the fuel canister in the boat, just to be sure!

In an inflatable boat that is barely the size of a bathtub, and

loaded with three people, it's not easy to make a group photo that includes

the photographer. But it can be done, with a long and very extended arm!

:-)

This morning it was slightly cloudy, but still there were no signs of

rain. And the sun was coming through from time to time.

We left the boat where the Porcelana river met the Porcelana bay, and

walked along the river, first along pastures, soon into the forest.

Soon we found steam

wafting through the air. That was a good sign! We followed the thickest

steam, and soon enough the water that trickled along the mostly dry riverbed,

which runs at a few meters distance from the main, very wet and very cold

river, became warm enough to walk barefoot in it.

Soon we found steam

wafting through the air. That was a good sign! We followed the thickest

steam, and soon enough the water that trickled along the mostly dry riverbed,

which runs at a few meters distance from the main, very wet and very cold

river, became warm enough to walk barefoot in it.

We continued slightly uphill, trying to find out where the warm water

came from, and found many small dispersed springs. The higher we got, the

more springs we found, and the warmer they were.

We had been told that after intense rains, the thermal springs were

flooded by the river. But now it hadn't rained for several days, the river

was low, and the springs were well exposed.

Finally we found

this to be the ideal spot for bathing. These pools had a good temperature.

Not nearly as boiling hot as the water from Cahuelmó, but warm enough

to be very comfortable. We spent some hours in the water, until we were

all shriveled up.

Finally we found

this to be the ideal spot for bathing. These pools had a good temperature.

Not nearly as boiling hot as the water from Cahuelmó, but warm enough

to be very comfortable. We spent some hours in the water, until we were

all shriveled up.

Take a look at these ferns! Many of them exceed two meters in length.

The rest of the vegetation is equally lush. It seems that the slightly

higher temperature and guaranteed humidity ensured by the warm spring helps

the plants grow especially beautiful.

After getting thoroughly wet, warm, clean and shriveled, we got dressed

and returned to the Capricornio. The day had still enough daylight hours left

for us to start our northward return, so we decided to set out for Cahuelmó

again and spend the night there.

At the entry to

the Cahuelmó fjord there is a large colony of sea lions. All the other

times we passed by that point, the animals were away fishing - I trust

they had more luck than we did -, but this time we found them at home,

playing, roughhousing, taking plunges, and singing their song in all kinds

of voices from the sopranos of the little ones to the ultra deep, somewhat

raspy bass of the big old males.

At the entry to

the Cahuelmó fjord there is a large colony of sea lions. All the other

times we passed by that point, the animals were away fishing - I trust

they had more luck than we did -, but this time we found them at home,

playing, roughhousing, taking plunges, and singing their song in all kinds

of voices from the sopranos of the little ones to the ultra deep, somewhat

raspy bass of the big old males.

When we got here, turning from the Comau fjord into Cahuelmó,

we got out of the wind. There was just the slightest imaginable trace

of any air motion. We left the engine off, and the Capt'n showed off his

truly good abilities in sailing a sloop in less wind than what we could

have blown ourselves. We sailed past the extensive sea lion colony, very,

very slowly, in complete silence except for the clicking of my camera,

at a distance so short from the rocks that I was a bit queasy about what

would happen if suddenly any significant wind turned up. But the

Capt'n was sure of his action, and the near pass gave me all the opportunity

I ever dreamed, to shoot sea lion photos!

The animals were not particularly upset by our presence. Some watched

us, others had more interesting matters to care about. When someone of

us had the bad idea to talk, however, that caused a general stampede into

the water! The older animals launched gracefully, belly-sliding down the

polished rocks and gliding elegantly into the water. The young ones instead

hadn't learned such elegance yet, and some of them tried to reach the water

from some higher lying rock, landing flat on their bellies on the next

rock below! It didn't seem to harm them the slightest bit. They joined

the others in the water, and then the whole colony decided that we were

not really dangerous after all, even if we talked, and they climbed their

rocks again.

The only one

who got slightly disgusted by the whole show was this vulture, accustomed

to eating the remains of fish, after the sea lions are satiated. The birds

use to sit on the tops of the rocks, waiting for something edible to be

discarded by the mammals. But this guy got all soaked when the sea lions

went into the water en masse and splashed like little kids, and now he

has to dry off his plumage in the late afternoon sun! His angry look towards

us tells the whole story!

The only one

who got slightly disgusted by the whole show was this vulture, accustomed

to eating the remains of fish, after the sea lions are satiated. The birds

use to sit on the tops of the rocks, waiting for something edible to be

discarded by the mammals. But this guy got all soaked when the sea lions

went into the water en masse and splashed like little kids, and now he

has to dry off his plumage in the late afternoon sun! His angry look towards

us tells the whole story!

We kept sailing

into Cahuelmó, with next to no wind, while the Capt'n served his

kitchen duty by preparing some junk food. At the end, we had no choice

but to fire up the Volvo Penta again, because this sort of wind

would have taken far into the night to bring us to our planned anchorage!

We kept sailing

into Cahuelmó, with next to no wind, while the Capt'n served his

kitchen duty by preparing some junk food. At the end, we had no choice

but to fire up the Volvo Penta again, because this sort of wind

would have taken far into the night to bring us to our planned anchorage!

Such low wind in mid winter is always a bit suspicious. We tried to

get a weather forecast on the radio, but didn't get contact to anyone.

Anyway, we did make eyeball contact with a few fishermen who strayed into

the bay, and they told us that there was a forecast of possible foul weather

in the evening of the following day, so they advised us to leave Cahuelmó

in the morning. They said that with really foul weather, it can be impossible

to get out of the bay, and that the place where we were anchoring could

turn bad too. But they also told us to enjoy a good night's sleep, because

there was no risk for the night.

We watched the barometer that evening, and it was dropping more than

usual. So we decided to set out early the next day, trying to get as far

as possible before the expected foul weather came in. After all, we had

return air tickets with fixed dates on them, and didn't want to loose them

by sitting out a storm for three days!

Our escape started

very nicely. We had strong south wind, which usually is an indication of

good weather. It was the ideal wind direction, and the good old Capricornio

felt a bit like a racing sloop! The barometer had stabilized, and so, despite

the cloudy weather, we were not overly worried.

Our escape started

very nicely. We had strong south wind, which usually is an indication of

good weather. It was the ideal wind direction, and the good old Capricornio

felt a bit like a racing sloop! The barometer had stabilized, and so, despite

the cloudy weather, we were not overly worried.

As we left the Comau fjord and came into more open waters, the sea got

so rough that our newly reinstalled autopilot could not keep the sloop on

course. The heavy waves from aft threw us off course, and much before

the autopilot's servo had locked to the right course again, the next wave came. So,

we were back to manual control, a task our Intrepid Boatswain enjoyed profoundly.

The dinghy, trailed by way of an elastic cord, was gliding on the water,

from one crest to the next, and we joked that it was about time that the

Capt'n purchased some water skis for times like this!

Do you know how you save freshwater and fill the kitchen sink, effortlessly,

with salt water? Well, you tell the helmsman to take the wind hard from

port. The boat heels over heavily, and if the sink plug is open,

water rushes in automatically through the drain line. When you have enough,

you put in the plug and tell the helmsman to return to the normal course,

the sloop rightens itself, and you can wash the dishes! It works like a

charm in wind like this!

After lunch time,

we came into an area with very strange-looking sky. The very shape of the

cloud protuberances told us that there were layers of strong winds in different

directions. The Boatswain measured the wind, trying to get any clues at

what would happen, and when. The wind wasn't very strong now, and the sloop

was going fine under full sail. Even so, the Capt'n decided to reef the

main sail a bit, to be better prepared for eventual gusts.

After lunch time,

we came into an area with very strange-looking sky. The very shape of the

cloud protuberances told us that there were layers of strong winds in different

directions. The Boatswain measured the wind, trying to get any clues at

what would happen, and when. The wind wasn't very strong now, and the sloop

was going fine under full sail. Even so, the Capt'n decided to reef the

main sail a bit, to be better prepared for eventual gusts.

We kept constant watch on the radio, trying to get some newer weather

forecast. But the sea seemed devoid of humans, within the reach of our

impaired radio. We did cross paths with one little fishing boat. The man

on board screamed something in our direction, but we couldn't understand.

We screamed back, asking what it was, he screamed again and continued his

trip, waving widely. Our interpretations ranged all the way from "Hello

guys, enjoy your trip!" to "Get the hell out of here,

before it's too late!" We called him on the radio, but got no

answer, which was expected because most of these fishermen have no radios

on their little open boats. So we had to decide what to do. Considering

that Rolecha was within not much more than one hour sailing at this speed,

and that alternative anchorages were plagued by shallow waters at their

inlets, the Capt'n decided to make the run for Rolecha.

And a while later the storm hit us. It came so violently and suddenly,

that it left us no time to react. A tremendously powerful gust pushed the

Capricornio on its side, causing a terrible mess under deck. Pointing into

the wind, we soon were upright again, but before we could take down the

sails, the main sail ripped and waved like old underpants held between

two fingers. With the main sail gone and the jib still up, the rudder

proved insufficient to keep control, and the wind hit us form the side

again. Only then we managed to free the jib, but that turned us into a

plaything of the storm and the waves. We fired up the engine and pointed

into the storm again. I had to exert real force on the helm, with wide

excursions to keep the vessel into the wind, while the Capt'n took down

the jib and the shreds of the main sail. Then things calmed down a bit,

but we realized that the waves were building up fast, and that the Volvo

Penta could barely push us against this wind!

A while later, the GPS showed us to be stationary, despite the engine

running at maximum emergency power. So, the Capt'n decided, for the first

time in the Capricornio's life, to set the tiny storm sail. There had never

been any need to use it, in the calm weather near Antofagasta! The storm

sail is a lot smaller than a wind surfer sail, and made of very thick fabric.

This sail gave us back some speed. The wind had turned north, so we had

to sail as close-hauled as possible. The engine was kept on full

emergency power, and together with the storm sail it gave us about two

knots of speed. The waves had build up enough that all the time water was

coming over deck. I need eyeglasses, and just couldn't keep them clear

enough to see, so I went down below, trying to overcome my tendency towards

seasickness, and babysitting the hard working engine while listening to

the VHF radio.

The Capt'n was proud of his brave yacht, and begged me to come up and

shoot some photos of the Capricornio under storm sail! But there was no

way to shoot photos out there, except with a submarine camera, which I

didn't have... So I stayed down below. I noticed that the bilge pump was

running almost nonstop. To my dismay I discovered that the hull was stressed

so much that sometimes the daylight, in addition to lots of water, squeezed

through between the individual planks! When I saw that, I took my

GPS, with spare batteries, the little handheld VHF radio, also with spare

batteries, packed it all in ziplock bags and stuffed it in my pockets.

After all, we still had the dinghy if the Capricornio broke up and went

down!

Too many hours

later, we managed to get into Rolecha bay. It provided decent protection

from the waves, but not from the wind. Still, it was the best place around,

as evidenced by scores of vessels of all sizes that had sought refuge here.

They welcomed us on the radio, and congratulated us for the bravery of

using a sail in this storm. Little did they know that it happened only

because our poor old Volvo Penta being too weak to handle such a situation

on its own!

Too many hours

later, we managed to get into Rolecha bay. It provided decent protection

from the waves, but not from the wind. Still, it was the best place around,

as evidenced by scores of vessels of all sizes that had sought refuge here.

They welcomed us on the radio, and congratulated us for the bravery of

using a sail in this storm. Little did they know that it happened only

because our poor old Volvo Penta being too weak to handle such a situation

on its own!

The problem was that the Rolecha bay has sandy bottom, and most of the

vessels were dragging their anchors. All the time someone would weigh

his anchor, motor a few hundred meters into the storm, then drop the anchor

again, only to be dragged back again. But our Capt'n was confident. He

said, quite modestly as is his trademark, that his anchor was the best

sand anchor in the world. We went to a place that was about 7 meters deep

(it was low tide) and seemed far enough away from other vessels, not an

easy task in this crowded place, and there the Capt'n dropped his sand

anchor, with 40 meters of nylon rode attached to its 30 meters of iron

chain, while I kept the vessel on spot with the engine. Then he took the

helm, cutting power and letting the storm push the boat back. WHAM! That

treatment made the anchor really bite into the bottom! It didn't

drag even one meter during the whole night!

Still, the worried face on this photo tells that we were not very comfortable.

Poor Capricornio shook like crazy. In the storm, the mast and shrouds entered

resonance, and the oscillations were so bad that we toyed with the idea

of stealing a chainsaw and cutting down the mast.

Amidst all this, we got hungry. We had been wanting to make pancakes

all along the trip, and now we had the perfect moment at hand to do it:

With the boat laboring so much, the pancakes flipped themselves! It was a simple

matter of waiting for them to jump high up into the air when a wave hit

the boat, and then catching them with the pan when they came down again!

When the next

morning broke, the storm was ending. Even so, the port authority delayed

our leaving until 11:30, because the sea out there was still quite rowdy.

We used that time to fix the mainsail as best we could. It ended up

reefed to half its normal area, but usable.

When the next

morning broke, the storm was ending. Even so, the port authority delayed

our leaving until 11:30, because the sea out there was still quite rowdy.

We used that time to fix the mainsail as best we could. It ended up

reefed to half its normal area, but usable.

The weather was still unstable, so we decided to take the longer route

to Puerto Montt, in the sheltered channels between the islands of the Reloncaví

bay. That would have us sailing deep into the night. We had to reach Puerto

Montt that night, or Michael would loose his air ticket. The Capt'n's and

mine were for a few hours later, so for us it wasn't that critical.

The dynastarter was weak that morning, it actually had trouble getting

the diesel to run. Later we found out that it had been damaged by running

for several hours at top speed in the storm, with a regulator that didn't

really regulate. Most of the solder joints at the collector had unsoldered

themselves. Still, after the engine started, the dynastarter did work acceptably

as a generator, with low but sufficient output, so we didn't worry much.

We used the sails whenever there was enough wind, and filled the voids

with the engine. When the night fell, the wind stopped completely, and

we did the last five hours under engine power, with full lights, autopilot,

GPS-based navigation according to waypoints measured on the map and entered

manually, and it all went very well. The only anecdote happened when during

my turn as lookout, at one time I found us to be on a head-on collision

course with some other vessel of which I could see just the lights. Not

fluent in marine customs, and being a paraglider pilot who knows that things

are not always as obviously simple as in street traffic, I asked the Capt'n

to which side I had to evade the other vessel. His interesting answer:

"I don't know! Let me check the rule books!" And the lights were coming

closer, fast!

Well, a moment before the Capt'n had found the relevant page, the vessel

ahead turned a little to his right. Oh, now I know! So I turned a little

to my right too. When he came close enough to see him, it turned out to

be a large Ro-Ro. It would not have harmed him much to run right over the

little Capricornio!

In defense of the Capt'n, I feel obliged to add that the answer he came

up with was indeed the correct one!

Forward to another trip on the Capricornio

Back to the homo ludens nauticus index.

Opening

my path into the bow cabin, I found another flashlight. It was heavy, which

meant that this one actually had batteries. Marvelous! But it didn't

work either... So, the problem could be the batteries, the bulb, or a contact.

I crawled back, found the other flashlight again, put the batteries of

the second one into the first, and Eureka, I had light!!!

Opening

my path into the bow cabin, I found another flashlight. It was heavy, which

meant that this one actually had batteries. Marvelous! But it didn't

work either... So, the problem could be the batteries, the bulb, or a contact.

I crawled back, found the other flashlight again, put the batteries of

the second one into the first, and Eureka, I had light!!!

It was in mid winter

2004 when my friend and then workmate Germán invited me to sail

to the Comau fjord aboard his yacht Capricornio. You will understand that

at first I was a bit reluctant to go, considering that the summer before,

on the boat's and the Captain's first trip in the complicate waters of

Chiloé, more than one thing went wrong, with no electricity of any

sort on board, no radio contact, no lights, no bilge pump, the boat taking

on water like mad, the hand pump breaking down, the mast almost going overboard

when the forestay broke, and a few dozen other interesting happenings of

the kind that add spice to the seaman's life.. But then, errhm, I

thought that these nice fellows would not survive another trip without

my valuable help, and said yes!

It was in mid winter

2004 when my friend and then workmate Germán invited me to sail

to the Comau fjord aboard his yacht Capricornio. You will understand that

at first I was a bit reluctant to go, considering that the summer before,

on the boat's and the Captain's first trip in the complicate waters of

Chiloé, more than one thing went wrong, with no electricity of any

sort on board, no radio contact, no lights, no bilge pump, the boat taking

on water like mad, the hand pump breaking down, the mast almost going overboard

when the forestay broke, and a few dozen other interesting happenings of

the kind that add spice to the seaman's life.. But then, errhm, I

thought that these nice fellows would not survive another trip without

my valuable help, and said yes!

It's

time for an introduction: This is the much bespoken Germán. From

now on we will respectfully call him "the Capt'n". Here he is showing his

impressive ability to give orders. The other main actor of this story,

Michael, will be often referred to as "The Intrepid Boatswain". You will

soon see why, so don't ask.

It's

time for an introduction: This is the much bespoken Germán. From

now on we will respectfully call him "the Capt'n". Here he is showing his

impressive ability to give orders. The other main actor of this story,

Michael, will be often referred to as "The Intrepid Boatswain". You will

soon see why, so don't ask.

We threw all the

purchases into the sloop, set sail and sailed out on the Tenglo channel,

then straight south across the Reloncaví bay. This map, artfully

drafted by fellow sailor Alfonso Gonzales for this story, shows the area and

a rough sketch of our trip. Basically, we went south to the Comau fjord,

and then along all its length, visiting the beautiful places along it, and

taking refuge in sheltered bays during the nights.

We threw all the

purchases into the sloop, set sail and sailed out on the Tenglo channel,

then straight south across the Reloncaví bay. This map, artfully

drafted by fellow sailor Alfonso Gonzales for this story, shows the area and

a rough sketch of our trip. Basically, we went south to the Comau fjord,

and then along all its length, visiting the beautiful places along it, and

taking refuge in sheltered bays during the nights. It had stopped

raining, the sun had come through, the wind was perfect, and we enjoyed

it. Most of the time I would sit at the helm. The Capt'n loves to hang

out at the bow, so that's what he did most of the time. Michael, instead,

is the kind of guy who can't stay put for more than five minutes. He was

milling around, stowing away our supplies, cleaning up, cooking, fixing

things, reading the map, navigating, and so on. Sometimes I tried

to switch places with him - but I didn't last! I have an easily upset stomach,

and when the vessel rolls and pitches like it loves to do when the wind comes

from near the stern, like here, I must stay on deck and look at the horizon,

or I would soon feed the fish. And so, if I have to stay on deck anyway,

I might as well hold the helm...

It had stopped

raining, the sun had come through, the wind was perfect, and we enjoyed

it. Most of the time I would sit at the helm. The Capt'n loves to hang

out at the bow, so that's what he did most of the time. Michael, instead,

is the kind of guy who can't stay put for more than five minutes. He was

milling around, stowing away our supplies, cleaning up, cooking, fixing

things, reading the map, navigating, and so on. Sometimes I tried

to switch places with him - but I didn't last! I have an easily upset stomach,

and when the vessel rolls and pitches like it loves to do when the wind comes

from near the stern, like here, I must stay on deck and look at the horizon,

or I would soon feed the fish. And so, if I have to stay on deck anyway,

I might as well hold the helm...

We sailed all

the way to Rolecha, a small village along a bay that offers good anchoring

ground and some protection. Soon the evening came, and on this photo you

can see how our first idyllic night on the Capricornio went: Working with

battery-powered headlamps to conserve the little remaining charge on the

main batteries, the whole crew is at work. The Boatswain was happily filing

away at a fitting he needed to complete an ultra-effective pump setup.

After the last trip, where he got duly fed up with hauling buckets, he

now wanted several pumps in good working order. The Capt'n is assisting

that noble effort, while I'm entirely devoted to the generator.

We sailed all

the way to Rolecha, a small village along a bay that offers good anchoring